The rise, fall and rise again of psychedelics

“To make this mundane world sublime,

Take half a gram of phanerothyme”

“To fathom Hell or soar angelic,

Just take a pinch of psychedelic”

And just like that, the word ‘psychedelic’ was created.

Marking the beginning for a new era in psychedelic research, the word ‘psychedelic’ was announced by Humphry Osmond at the New York Academy of Sciences meeting in 1957. ‘Psychedelic’ was to be the new word to describe the effects of drugs such as mescaline or LSD, which up until then could only be described through words like hallucinatory or psychotic, all too loaded with negative connotations. The idea was to have ‘psychedelic’ as the less harsh substitute, free of connotations and truly objective. Now, when the positive sides of these substances were starting to be discovered, it was necessary to bring objectivity to the table and eliminate the negative cultural connotations associated with the drugs.

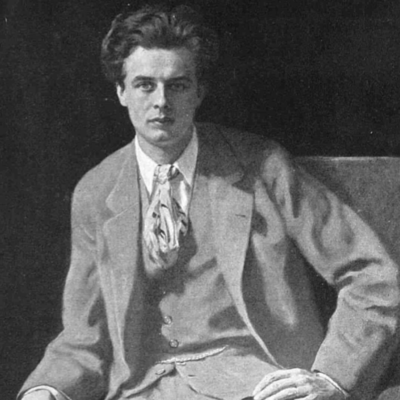

How the word came to be

The word came out of a letter exchange between Aldous Huxely and Humphry Osmond, who first spotted the need for a word change in the science community. Whereas Huxley wanted it to be ‘phanerothyme’, from the Greek words for ‘to show’ and ‘spirit’, it was Osmonds suggestion of ‘psychedelic’ from the Greek words ‘psyche’ (mind) and ‘deloun’ (to show) that ended up making its way to the scientific community. Since 1953, the two had been in constant communication regarding their experimentations with mescaline and other psychedelic substances. In fact, their letter exchange started precisely when Huxley, after reading an article by Osmond, sent him a letter asking to try mescaline.

The times in which both lived were those of change. In a post-war atmosphere, the use of psychedelic substances had become the gateway to new imagined worlds. From spiritual to scientific realms, psychedelic substances were suddenly becoming the centre of attention for some. LSD, which had just been discovered in 1938, was slowly gaining prominence amongst the curious minds. Mescaline, which had been known for a very long time, was suddenly being rediscovered by those in the arts and sciences.

First encounter with the drugs

First time Osmond came in touch with mescaline and LSD was during his time at the St. George’s Hospital in London, where he had gotten a psychiatric position. There, together with another psychiatrist called John Smythies, he came to study the effects of mescaline and their similarity with what was observed in schizophrenic patients. Soon after John Smythies arrived at St. George’s Hospital, he noted that the molecular configuration of mescaline was very similar to that of catecholamines neurotransmitters. This similarity immediately caught his attention as, perhaps, it could suggest that schizophrenia, which seemed to lead to symptoms similar to those of mescaline, could be caused by abnormalities in the catecholamine metabolism. The hypothesis that arose from this observation was one of the first biochemical hypothesis for schizophrenia.

The transatlantic move

Excited about this new hypothesis, both Osmond and Smythies soon started to focus more and more on the biochemical causes of schizophrenia. Experiments involving mescaline became ever more common and the self-administration of the drug became to them the gate to the patients’ minds. Despite their efforts and relatively successful results, nevertheless, the British scientific community saw their work with little enthusiasm. Hence, in 1951 Osmond decided to move to Canada (Saskatchwan), where he could proceed with their work at the Wyburn Mental Hospital, with funding from the Canadian government and the Rockefeller Foundation. There, the experimentations continued and after a year of work, in 1952, he published an article in collaboration with Smythies on which they presented their findings.

A space for inventions

The Wyburn Mental Hospital represented a new stage in Osmond’s career. There, after assuming the clinical director role, Osmond transformed the hospital into a design-research laboratory where a series of experiments and observations regarding the use of psychedelic drugs were made. During those years, Osmond and Abram Hoffer, a Canadian biochemist and psychiatrist, further improved their ideas regarding schizophrenia and developed new hypotheses regarding the possible use of LSD as treatment for alcoholics. Furthermore, Osmond put in motion a total change in the ways psychiatry was thought of at the time. After participating in a peyote ceremony with the Native American Church, Osmond came to the realization that the space in which the patients were living was also affecting, even worsening, their symptoms. Hence, he then decided to put some effort into the construction of safer architectural spaces, which he coined ‘socio-architecture’, now known as ‘environmental psychology’.

To achieve his goal of an architecture made specifically to accommodate mentlly ill patients, Osmond invited architect Kiyoshi Izumi. What came next was one of the most remarkable projects in architecture of the time. As the goal was for Izumi to design a space suitable for those suffering from hallucinations, Osmond suggested that, perhaps, it would be a good idea for Izumi to experience the hallucinations himself. What followed was a number of different sessions in which the architect, who up until that point had not much experience with psychedelics, would take ‘the quixotic giant’, how Osmond called LSD, and stroll around the building in order to experience what the patients would experience. From the multiple LSD trips and from many conversations with patients, Izuki came to design what he called the ‘sociopetal’ plan: the near-perfect mental hospital.

The main goals of the design were to provide as much privacy as possible, minimize architectural ambiguity, bear no intimidating features and foster spatial interactions that curtails the frequency and intensity of undesirable confrontations. Unfortunately, however, the design was considered too ‘radical’ by the Department of Psychiatric Services and the building codes. A ‘reinterpretation’ of the design had to be made, accommodating the feedback from the others involved. The final design,for the untrained eye, looked still much like a standard building of the time. At a more careful look, nevertheless, one would soon realize the small changes that had been made. Rooms were specifically made so that patients could feel safe and not observed. Clock and calendar were carefully placed around the building to ensure that patients did not feel lost in time. Sources of heat, light and sound were all designed to avoid creating confusion. All thought of with the help of psychedelics.

The meaning of the word: psychedelic

For Osmond, substances like LSD and mescaline were a bridge between patients and doctors. They facilitated the communication between the two and made the patients feel less lonely in their world. For him, it was fundamental that those working with the patients, be it doctors, nurses or architects (like was Izuki’s case) had some understanding of what went through their mind. In psychedelics he saw both a way to be closer to some of the patients and a treatment to some illnesses. For instance, between 1954 and 1960, Osmond and Hoffer managed to treat about 2000 alcoholics using LSD. From those treated, 40% to 45% had not returned to drinking a year after.

It was a shame that, some years after Osmond’s research had started, it suddenly had to come to a halt due to political reasons. In the 1960s, regulations regarding substances such as LSD started to arise and research on the drugs was made almost impossible. The word ‘psychedelic’ which had come with the intention of counteracting the negative connotations of the drugs, had become itself a negative word once again. For years, Osmond’s research was left forgotten and the history of what it had created erased. Recently, however, with the rediscovery of the beneficial effects of psychedelics, Osmond’s work has finally started to see light again. Now, almost 30 years after his death, the work of Humphry Osmond is back to life and, with it, the hope for a new form of psychiatry and a new understanding of the human brain.

Did you enjoy reading this article and do you like to write yourself? We are always looking for people who share our passion for natural products, who can also translate this into great texts. And we have an interesting reward for this. View all information for writers.

Atlantis

Superior Quality New! Blog Psychoactive Plants

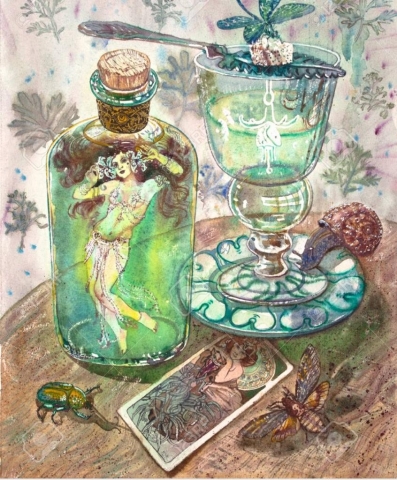

Absinthe: Looking for the Green Fairy

Unless you've already heard about it, you're probably wondering what the Green Fairy is. Many artists (such as Degas, Picasso, Van Gogh, Rimba [..]

20-02-2023

8 minutes

Blog Psychoactive Plants

Absinthe: Looking for the Green Fairy

Unless you've already heard about it, you're probably wondering what the Green Fairy is. Many artists (such as Degas, Picasso, Van Gogh, Rimba [..]

20-02-2023

8 minutes

Blog User Reports

My Experience with CBD Oil: Reducing Anxiety with Cannabidiol

My personal experience with CBD, or cannabidiol. By discovering CBD products, I learned to better cope with fear of failure and was able to relax my b [..]

16-02-2021

9 minutes

Blog User Reports

My Experience with CBD Oil: Reducing Anxiety with Cannabidiol

My personal experience with CBD, or cannabidiol. By discovering CBD products, I learned to better cope with fear of failure and was able to relax my b [..]

16-02-2021

9 minutes

Blog Mescaline Cacti

What is the best way to consume the mescaline cactus San Pedro?

The other day someone told me about his trip with San Pedro, together with a friend. It was a life-changing experience in which he came very close to [..]

Blog Mescaline Cacti

What is the best way to consume the mescaline cactus San Pedro?

The other day someone told me about his trip with San Pedro, together with a friend. It was a life-changing experience in which he came very close to [..]

Nederlands

Nederlands Italiano

Italiano Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français Português

Português Español

Español Polski

Polski